Consider two pretty obvious statements. First, living in dense cities is much more energy efficient than living in rural areas, especially in cold places where you need heating. Second if we had 1,000 cities the size of New York City, that would be all of humanity, and they would only occupy a small fraction of the earth's surface. A somewhat larger fraction would be used for producing food and extracting some resources but the vast majority of land on earth could be devoid of humans. Yet, for years, I've been surprised at how often people are surprised by these points. Somehow, people assume that cities are bad for nature and that living in a rustic rural cabin or hut, using wood fires for energy is more friendly toward nature. Obviously the flaw in such reasoning is that they are thinking not of humanity as it exists today or in the future, but subconsciously going back to a time when there were very few humans, and so it didn't matter if we were extremely wasteful of resources. Of course the reason there were few humans is that most of them died very quickly. It's a "wet streets cause rain" type of reasoning that is surprisingly prevalent.

Another bit of inanity is that many people believe using bio-fuels is "good for the environment". Indeed the US government mandates blending corn ethanol in gasoline. This is good for corn farmers, and good for politicians who depend on them, and maybe even good if you think foreign oil is a problem. But in fact, when compared to just using gasoline without corn ethanol, it results in an increase in green house gas emissions, not a decrease. Yet the belief that it's good for the environment persists.

A new book, Apocalypse Never, by Michael Shellenberger covers these as well as many other such points, in making a very good case that the current global alarmism around climate change is doing more harm than good. Normally, the title and the marketing of the book would have turned me off. The last thing I want is more political BS from climate change deniers. But this book is not that at all. The author not only agrees with the conventional view that the climate is changing due to greenhouse gas emissions, but he's actually one of the pioneers in the space. Second what actually made me notice the book in the first place was that people were trying to get it banned or de-platformed. Which naturally kind of proves the point that he's making. And it made me want to look into it. (So maybe giving it a provocative title is a good strategy after all!). Which I don't regret.

He also does a good job debunking the idea of "extinction of humanity". Of course we won't go extinct because of global warming. Isn't it enough to say it will cause a huge problem and enormous suffering? Similarly "saving the planet" is misguided hyperbole. The planet will still exist, even if it's boiling hot or completely frozen, and certainly more CO2 in the atmosphere and temperature changes of a few degrees are no big deal on a geological timescale. So this is just misguided and confused language that is counter-productive. It's like when people scream about "genocide" whenever there's some political violence or war that is ethnically motivated. Constantly calling everything a genocide is not helping the cause of peace. Similarly saying that smoking a joint is exactly the same as a heroin overdose is not helping kids avoid drugs.

If you care about solutions and the well-being of humanity, you should be more precise in your thinking. What we care about is how we live, and what we mean by "we" is critical. The book does a good job of explaining this and the underlying basic concepts, perhaps the most important of which is "energy transitions", and he generally summarizes the science and arguments pretty fairly

Still there are a few points where I disagree with it, three in particular.

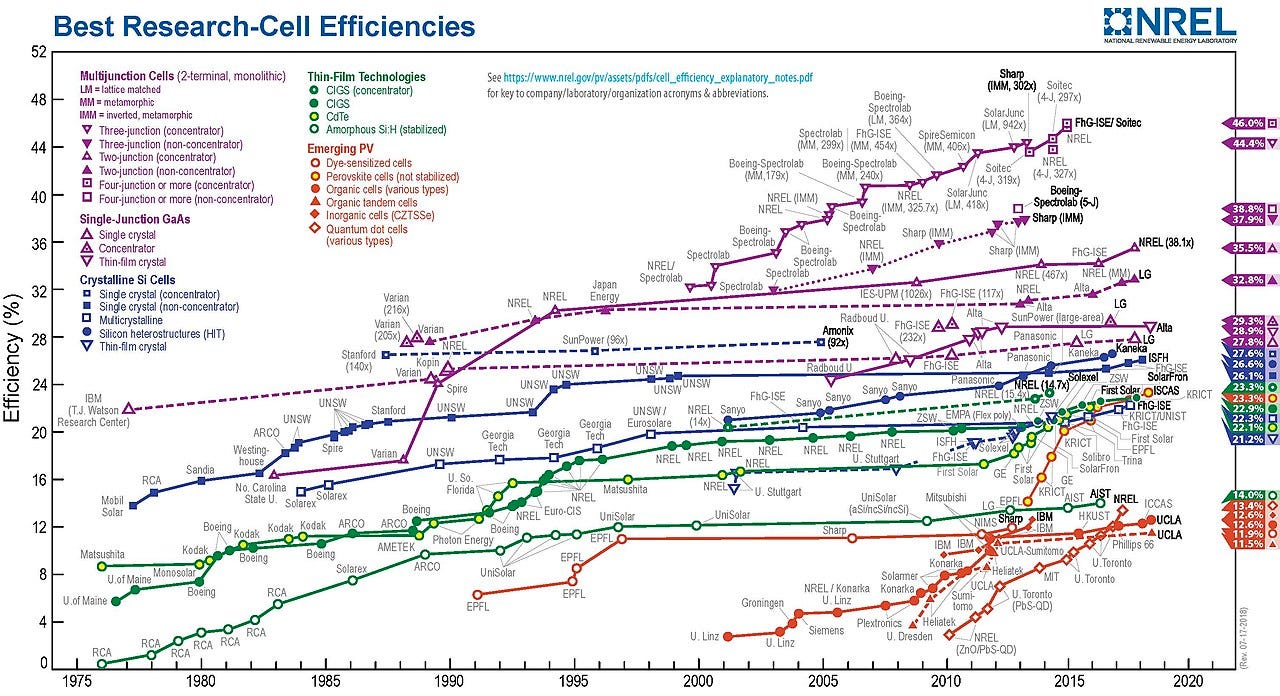

The second one is a much more serious problem. In discussing solar power he says "the achievable power density of a solar farm" is "up to" 50 watts/m2 (p. 188). But the solar constant is 1 .37kw/m2 and the maximum solar energy on the surface of the earth is about 1,000 watts/m2. So he's assuming solar conversion achieves 5% efficiency at best. But this is not true, as we can see from this chart, we're at about 20-30% now and gaining about ten percentage points per decade, as I've written about before. So his take is really unduly pessimistic about the future of solar power.

.37kw/m2 and the maximum solar energy on the surface of the earth is about 1,000 watts/m2. So he's assuming solar conversion achieves 5% efficiency at best. But this is not true, as we can see from this chart, we're at about 20-30% now and gaining about ten percentage points per decade, as I've written about before. So his take is really unduly pessimistic about the future of solar power.

Third, he makes a really good case for nuclear power for electricity generation. But he fails to address what to me is the strongest argument against it. Chernobyl and Fukushima are "supposed" to happen once every few hundreds of years. But if we do a Bayesian update on those priors, the probabilities are much worse than advertised. Or to put it more simply: How come no nuclear power plant can get private insurance? If the risks are as low and manageable as he and other advocates claim, then one should be able to get free market insurance for it. But that has never happened. I used to be pro-nuclear power, but I've become more skeptical over the years. And despite devoting a lot of the book to it, Schellenberger didn't quite convince me.

Overall, this is a good book, it helps the reader think of many of the questions in a more holistic way, and paints a coherent big picture of environmental humanism. Recommended reading.